HTTP Request/Response

Understanding the Request/Response exchange between browsers and web servers is critical for a good insight on coding web applications. What is client-side code? What is server-side code? How does the browser communicate with the web server? And can the web server communicate with the browser directly? There’s a lot to learn….

The Great Exchange

Section titled “The Great Exchange”Web browsers work by requesting resources (pages, images, style sheets, etc.) from web servers. Web servers are simply computers that work to respond to requests for resources.

The protocol that web browsers use is called HTTP, which stands for Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol. Essentially, it’s a mechanism that allows computers to communicate via simple “text” information.

Not only does the browser send requests via text, the web server responds with text. The response comes in two parts: The header and the body. Note that when we talk about the HTTP response “headers”, that is not the same thing as the <head> of an HTML document. The body of the response may be an HTML document, a CSS file, a JavaScript file, an image (as text), etc. But the common aspect to all of it is that data is transfered as text.

Here’s an example of a browser request given as raw text:

GET /CPSC-1520/ HTTP/1.1Host: dgilleland.github.ioReferer: http://base64.guru/tools/http-request-onlineAccept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8,application/signed-exchange;v=b3;q=0.7Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br, zstdAccept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9,en-CA;q=0.8Cache-Control: max-age=0Connection: keep-aliveUser-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/141.0.0.0 Safari/537.36 Edg/141.0.0.0sec-ch-ua: "Microsoft Edge";v="141", "Not?A_Brand";v="8", "Chromium";v="141"sec-ch-ua-mobile: ?0sec-ch-ua-platform: "Windows"Here’s an example of the web server’s response (header information only):

HTTP/1.1 200 OKConnection: keep-aliveContent-Length: 9971Server: GitHub.comContent-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8Last-Modified: Sun, 26 Oct 2025 06:11:43 GMTAccess-Control-Allow-Origin: *ETag: W/"68fdbb9f-8d61"expires: Sun, 26 Oct 2025 19:48:47 GMTCache-Control: max-age=600Content-Encoding: gzipx-proxy-cache: MISSX-GitHub-Request-Id: 768C:508FE:1915C39:196EF0F:68FE78C7Accept-Ranges: bytesAge: 0Date: Sun, 26 Oct 2025 19:38:47 GMTVia: 1.1 varnishX-Served-By: cache-par-lfpg1960022-PARX-Cache: MISSX-Cache-Hits: 0X-Timer: S1761507527.249471,VS0,VE129Vary: Accept-EncodingX-Fastly-Request-ID: 8cfa413270178bc047e34e869bd53346a8f96429Resource Types

Section titled “Resource Types”A lot of the time, we might think that our HTML page is “the thing” that’s being requested by the browser. But that’s hardly the case. While an HTML page is usually the first item requested, it is hardly ever the last.

Think of it. Our HTML markup indicates other resources that are part of the “page”: Stylesheets and Fav Icons (<link> tags), JavaScript files (<script> tags), and Images (<img> tags) make up much of what our HTML markup tells the browser to include. And each one of those resources must be requested individually by the browser. While the browser might begin rendering (drawing) the HTML right away, it won’t finish the whole job until the last of those resources is retrieved.

Request Objects

Section titled “Request Objects”You would probably be surprised at how much information your browser is sharing with the web server when it requests a resource. That includes data about the browser version, your operating system, your location (IP Address), “cookies”, and sometimes a whole lot more. This is information that the browser sends to the web server so that the web server can give you an appropriate response. This is the “public” exchange of data that goes over the internet.

When the protocol is HTTP, all that information is sent as plain text. When you ask for HTTPS, your information is sent (and received) as encrypted text (giving you a measure of privacy, however small that might be).

Response Objects

Section titled “Response Objects”A key aspect of the response of a web server is the status code of the response. Status codes fall into certain groupings.

| Status Group | Meaning | Most Common |

|---|---|---|

| 1xx | Informational | 100 - Continue |

| 2xx | Successful | 200 - OK |

| 3xx | Redirection | 304 - Not Modified |

| 4xx | Client Error | 404 - Not Found |

| 5xx | Server Error | 500 - Internal Server Error |

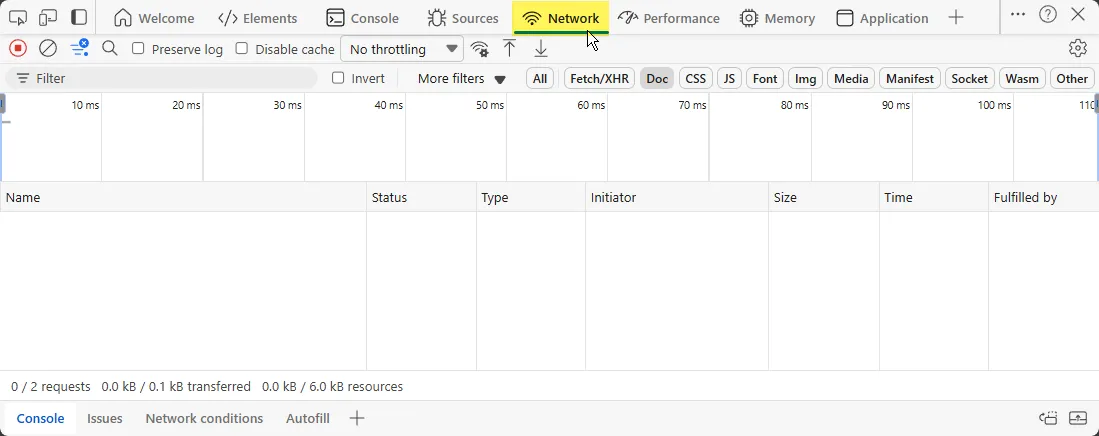

Exploring with the Dev Tools

Section titled “Exploring with the Dev Tools”There’s a “Network” tab in your browser’s Dev Tools. With it, you can record and inspect a wide range of network activity taking place when your browser communicates with the web server.

You can even simulate network “latency” with the Throttling drop-down. This can be helpful if you want to see how your page is rendered when you are on limited connections.

About Dev Tools

Section titled “About Dev Tools”There’s always lots to learn about the Dev Tools in your browser. Most browsers (despite their branding differences) use the same underlying engines. They fall into several families:

| Common Family Name | Rendering Engine | Major Browsers |

|---|---|---|

| Chromium-Based | Blink | Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Android WebView, Opera, Brave, etc. |

| Firefox Family | Gecko | Firefox, Tor, LibreWolf, etc. |

| Apple Ecosystem | WebKit | Safari, GNOME Web |